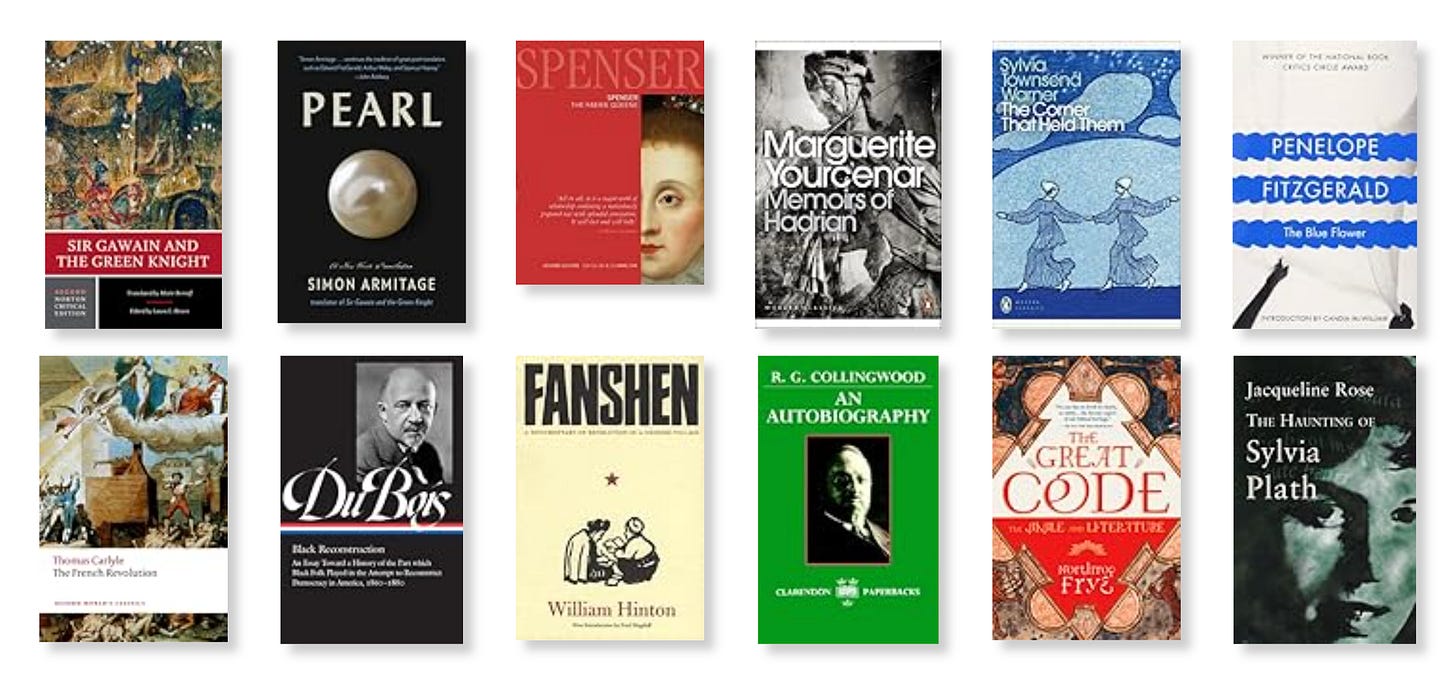

Books I Have Enjoyed

(Mostly recently, and also not so recently)

What would the end of the year be without a piece of retrospection? As the enshittification of the website formerly known as Twitter proceeds apace, I have been lax in keeping up my usual thread of books read throughout the year. To get back up to speed, this post condenses the past two years in a dozen books that I have enjoyed reading; divided equally between poetry, novels, history, and criticism. I have already written about some of these works on this blog, and would like to discuss others at length in the future, but for now let this be a taste.

The Poetry

The Middle English romance of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight begins on Christmas Eve in King Arthur’s court, where the celebrations are interrupted by the visitation of a gigantic and uncanny knight, who wears green armour, sports a green beard, and rides a green horse. The knight challenges the court to a Christmas game, which Arthur’s nephew Gawain accepts: the knight will accept a blow from Gawain, if Gawain will meet the knight a year hence to accept the same blow in return. When Gawain lops off the knight’s head he is revealed as the dupe: the knight retrieves his head, remounts his horse, and reminds Gawain of his promise; to fulfil his duty and forsake his life. Gawain’s ethical dilemma is redoubled in the middle section of the poem, which relates his stay in the House of Hautdesert, where the lord of the manor proposes another game: he will go hunting each day and grant his spoils to Gawain, if Gawain will grant to the lord all that he wins at home. When the lady of the house visits Gawain and insists upon the courtesy of a kiss, he is once again caught in the shameful comedy of fulfilling contrary duties. I’ll not say where the tale ends up, having written about it at length elsewhere, except to say that its tragic frame may yet be defused in Gawain’s comedy of manners. After all, what is a kiss or three between friends?

The manuscript that contains Sir Gawain and the Green Knight includes three other poems: two homiletic poems on the virtues of Patience and Cleanness, and allegorical poem known by its central figure as Pearl. The poem relates a dream-vision, experienced by the narrator as he sleeps upon the hill where his daughter is buried. In his dream, he meets his child, the eponymous pearl, in the heavenly city, where she tries to explain her life in the beyond. Where the poem could become didactic like Patience and Cleanness, it instead enters a tragic mode, as the dreamer experiences the mismatch between his earthly understanding and the order of the absolute. At each turn of their dialogue, the maiden’s instruction is misunderstood by the dreamer, who cannot make sense of the heavenly city in his own terms. Her explanations do not resolve but redouble his confusion; they do not speak in the same measure. In one of the most moving passages in English literature, the dreamer’s incomprehension confirms what the vision should assuage: the daughter he knew in life really is gone, never to be retrieved. Though the attempt to make sense of heaven fails, the poem conveys through this failure the agony of loss, which defies plain language and speaks in its ruin. I have written more on Pearl and its poetics of sorrow here.

By a strange coincidence, and against its reputation, the longest poem in English literature may also be one of the most entertaining. My experience of reading Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene struck me on three levels. Firstly, at the level of form, Spenser achieves a remarkably consistent quality of poetry, its pace helped by the versatility of his stanzas, the end couplets of which punctuate the cantos like a second order of metre. Perhaps it goes without saying that the Faerie Queene is a great poem, though this greatness is not only due to its mass, as it rewards equally in the inventiveness of its wordplay and syntax. Secondly, in terms of plot, the narrative surprises in both its eccentricity and intensity, as Spenser’s knights spiral away from their stated quests in digressions that dissolve and redouble the themes of each book. As each adventure is episodic, and each canto largely a self-contained tale, the book incorporates a range of material that is by turns bizarre, ridiculous, unsettling, and gripping. Finally, these episodes are tied together on a conceptual level, where Spenser’s metaphysical frame is constructed as a grand architectonic, joining disparate tales across hundreds of pages to form a densely woven treatise on virtue. It is on this level that the subtlety of Spenser’s allegorising becomes visible, as he refuses the view of allegory as a simple identity of moral and tale, and instead shows how the exposition of virtue must complicate itself. Though from one canto to the next the knights are diverted from their quests, the virtues they represent are not tarnished but purified by these tests, set out more clearly in their perfection against the backdrop of human error.

The Novels

Marguerite Yourcenar’s Memoirs of Hadrian is a literary séance for the dead emperor, written over several years in a daily ritual, whereby the author, having pored over the extant documents of Hadrian’s lifetime, composed fragments in his voice, collaborating with the shade to record his thoughts after centuries of oblivion. The conceit of the work comes from a remark by Flaubert concerning the unhappy consciousness of the first and second centuries: “Just when the gods had ceased to be, and the Christ had not yet come, there was a unique moment in history, between Cicero and Marcus Aurelius, when man stood alone.” Hadrian lived in an antiquity already ancient, deprived of the myths that had informed its classical past, without promise of a world beyond this one. The one figure of transcendence is Hadrian’s lover Antinous, whose death before his twentieth birthday saves his beauty from the decay that everywhere reigns, and whose deification by imperial decree preserves his memory against history. In all this, Hadrian conveys a spirit that is fallibly human, lacking the perspective of universal salvation and the stability of stoic self-mastery, knowing itself as an interval between eternities.

Sylvia Townsend Warner’s The Corner That Held Them is a case study in futility. The novel follows a medieval convent in the decades between the Black Death and the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, the years of which are passed by the nuns in a state of motionless tension. In seclusion from the world, these women live inactive lives, without the means to change their social standing or personal destinies; yet without capacity for action, neither have they recourse to the vita contemplativa, as their devotions float free of all worldly concerns, taking on a form without content. If this synopsis is abstract, it is because Warner’s novel is one of those rare works in which nothing happens, at least at the level of the plot, though the narrative proceeds without any loss of tension. Put another way, the life in the convent is structured around what does not happen, the absence of an event that would put these women’s lives in motion. Instead, the narrative eddies between focal characters, whose ambitions are masterfully rendered though they come to naught, and plots, which gradually let out momentum as the moments of their realisation are missed. What Warner achieves through this exercise in frustrated expectation is a portrait not of any one person, or even the institution to which they belong, but the long span of history that surpasses the perspective of either.

The life of the artist is lived in denial of the world, though the world encroaches upon them from all sides. Such is the lesson of Penelope Fitzgerald’s The Blue Flower in its fragmentary account of the youth of Fritz von Hardenberg, later acclaimed as the poet Novalis, and his doomed engagement to Sophie von Kühn. Though ostensibly about the poet, the novel is rarely focalised to his perspective, which appears to those around him as a mystery, informed by a poetic spirit that refuses explanation. In the poet’s works and utterances, the titular flower looks large as his symbol of the absolute, which the imagination constructs above and beyond the expanse of earthly time. Yet Fitzgerald does not let the genius hide within himself, as she contrasts his impossible ideal with the minutiae of prosaic and domestic life, which he disregards but cannot escape. When death comes for the Kühns and the Hardenbergs, the poet’s depths of experience become shallow, his mysteries become obtuse, and his pursuit of love itself a flight from the deathbeds of those he loves.

The Histories

The historian is typically considered an impartial observer, a conveyor of facts, at most a dutiful sifter of information into heaps labelled ‘Important’ and ‘Insignificant.’ One supposes that one reads history (the genre) to learn something of history (the past), while the task of the historian is to facilitate this learning in as engaging, though unobtrusive, manner as possible. At least, such is the view of a certain Mr. Dryasdust, whose page is heavy with such details, in another writer’s phrase. An opponent of Dryasdust might strike out in another direction; declaring that the purpose of history (again, the genre) is not to fill one’s spreadsheets with bits and bites of a mildewed heritage, but to encounter the variety of human experience, no matter how alien at a first glance, as one’s own. This is the spirit that motivates Thomas’s Carlyle’s The French Revolution, which takes as its models the poetic immediacy of ancient epic and the subjective irony of the Romantics. On the one side, Carlyle’s history revives the epic mode in all its severity, both in its attitude to its subjects, who charge to and fro as bit players in a collective drama; and in the severity of its style, which forgoes the readerly comforts of explanation and context to present its narrative in bare, paratactic sequence. On the other side, the historian’s objective view is dispersed in the ironic amassment of perspectives, as the cast of aristocrats, burghers, Sanscullotes, and regicides vie for sympathy, though each are destined to be equal in the end. In this twilight of the old regime, we may declare with Goethe’s Mephistopheles that all of this world deserves to perish.

W.E.B. Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction is an essential work on American capitalism, which asserts the pivotal role of Black workers in winning both their freedom and the Civil War, and dissects the counter-revolution of property which has not ceased to diminish the cause of emancipation. To err on the side of brevity, Du Bois’s work may be summarised in three theses: 1) The Confederacy’s war was lost by a mass withdrawal of enslaved labour, which, having been proletarianised by the consolidation of the plantation system, was the main agent in the collapse of the South’s wartime economy. 2) The Union’s war was won by the entry of Black workers into the Union army, making the army an instrument of slave revolt and radicalising the Union cause for emancipation. Though the Union generals did not plan for the general emancipation of captured territories, they were given an ultimatum from below: spill more blood in defense of ‘property,’ or emancipate and mobilise the freedmen of the South for the Union cause. 3) Reconstruction was the perpetuation of the slave revolt as a revolutionary movement, uprooting the social, political, and economic bases of the slavers’ state—though it ultimately tended toward a confrontation with property rights as such, including those of the industrial-capitalist northern states, which smothered the workers’ movement that had been born from the ashes of the old South.

William Hinton’s Fanshen recounts the process of land reform at the end of the Chinese Civil War and the abolition of the landed gentry’s regime along with their property relations. Whereas Du Bois surveyed the fate of millions across half a continent, Hinton’s narrative is focused on a single village in rural China, where the peasantry were tasked with determining their own fates in the re-establishment of political order. As an observer of these events, Hinton delivers a history in dialogues, recounting the to and fro of public meetings and private discussions as the villagers find what it means to govern themselves. What results is a dialectic of collectives, which must learn to judge the lines of class division; which decide the balance of political sovereignty between the peasants, the Party’s working group, and the reactionary forces; which discover the inclusive disjunction of violence and education in the revolutionary reshaping of the world. “Can the sun rise in the west?” was the mocking question of the gentry, who saw their regime as an extension of nature, unaware of history’s capacity to overturn all that seems fixed for eternity.

The Criticism

R.G. Collingwood’s Autobiography is a confession without a person, the reflections of an intellectual life struggling toward a practical philosophy that might grant it a world. This is not how Collingwood frames his book, though it is hard not to read between the lines, to see where reflections on the vita contemplativa border upon other modes of thought and action. Of especial interest to a newcomer to Collingwood’s philosophy will be the chapters summarising his historical theory of re-enactment and his method of metaphysical analysis. In the former case, history for Collingwood is not a recounting of facts but a reviving of past mentalities for our present understanding: though one can say that Caesar crossed the Rubicon on such-and-such a day, it remains to be discovered why he did so and how the content of his act may be conceptually significant for us. In the latter case, Collingwood refuses to equate metaphysics with an ontology of first principles, instead seeing it as an investigation of presuppositions; that is, metaphysics is not a question of ‘What is first of all things?’ but ‘What precedes this discourse?’ These theories are elaborated elsewhere in Collingwood’s oeuvre, but in the Autobiography take on a new significance. In re-telling a life, one must know how to make an account of oneself, how to bring the past to mind, and how to select the right place to begin. Hence, the Autobiography is less an account of a life than a meditation on self-discovery, as belated as it may be.

The subtitle of Northrop Frye’s The Great Code makes a syntactic distinction: it will not be a book on ‘the Bible as literature,’ which would entail some identification with the tenuous category of literature, but on ‘the Bible and literature,’ or the expansive relation between the texts that make up the Bible and the patterns of influence they exercise over subsequent writings. Frye’s approach is informed by the Viconian typology of discourses, in which the history of a culture may be mapped by its predominant rhetorical tropes, from poetic metaphor to the logical subordinations of synecdoche and metonymy, to the discursive instability of irony. Which is to say that a text that has survived through each of these stages has lived many lives, because the same words, the same phrases, do not have the same meaning across history. When Frye turns to the discussion of myth and its place in a culture, this attention to the malleability of meaning lifts him above the mythic criticism of a Jung or a Campbell. Considered as a form of language, a myth is not an originary truth, not a mystical discourse from before history, but a common figure expressive of a culture’s basic presuppositions. Hence, by putting aside matters of doctrine and contextualising the function of myth, The Great Code undertakes the critical task of identifying the figures that structure the Biblical text and their influence on wider cultures of meaning-making.

The maxim that ‘the personal is political’ has lost some of its novelty, though Jacqueline Rose’s The Haunting of Sylvia Plath shows that it need not have lost its provocative edge. Principally, Rose’s book is an outstanding work of psychoanalytic criticism, the terms of which do not paper over political or textual problems, but give a framework for the close reading of both Plath’s archives and the controversy of her reception. The object of criticism here is not exactly the author, much less her ‘psyche’ as divined from her poetry, but the psychic mechanisms of investment, displacement, and transference that intercede upon even the most critical readers and mediate their encounter with the work. The study of Plath’s early reception reveals the problematic place of the ‘woman poet’ in the discourse of ‘50s and ‘60s Anglophone criticism, which is not wholly resolved in the feminist recuperation of ‘confessional’ poetry through the ‘70s and ‘80s. In both contexts, the person of the poet is presumed as a presence that the critic may discover in the text—though in truth everything except a fixed personality is dredged up by the prying critic. In a rebuke to those for whom ‘the personal is political’ reduces the latter to the former, Rose shows that an attentive reading of the personal opens onto the political and historical dimensions of the work (or, in the older language of allegory, we may say that neither the literal nor the moral meanings are exclusive of the anagogical; the text is complex, and each of these meanings is coextensive to the others).